Page 117 - Profile's Unit Trusts & Collective Investments - September 2025

P. 117

Investment risk Chapter 6

The Sharpe ratio is a direct measure of the amount of reward for each unit of risk. It helps to answer

the logical question: was the return achieved worth the amount of risk taken?

The calculation of the Sharpe ratio can be thought of in two steps:

R Step one is the calculation of a portfolio’s “excess” return above that of a “risk-free” investment.

This is calculated by taking a portfolio’s average annual rate of return and subtracting a risk-

free interest rate. This figure shows the “excess” return that a fund has achieved, and is also

known as the “risk premium”.

R Step two shows the relationship between the risk premium and the level of risk taken. This is

calculated by dividing the excess return by the fund’s standard deviation. Obviously, the higher

the Sharpe ratio the more favourable the risk/reward profile of the portfolio.

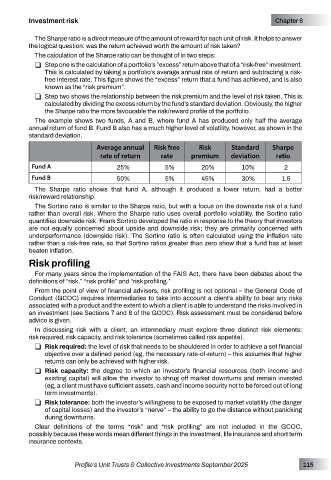

The example shows two funds, A and B, where fund A has produced only half the average

annual return of fund B. Fund B also has a much higher level of volatility, however, as shown in the

standard deviation.

Average annual Risk free Risk Standard Sharpe

rate of return rate premium deviation ratio

Fund A 25% 5% 20% 10% 2

Fund B 50% 5% 45% 30% 1.5

The Sharpe ratio shows that fund A, although it produced a lower return, had a better

risk/reward relationship.

The Sortino ratio is similar to the Sharpe ratio, but with a focus on the downside risk of a fund

rather than overall risk. Where the Sharpe ratio uses overall portfolio volatility, the Sortino ratio

quantifies downside risk. Frank Sortino developed the ratio in response to the theory that investors

are not equally concerned about upside and downside risk; they are primarily concerned with

underperformance (downside risk). The Sortino ratio is often calculated using the inflation rate

rather than a risk-free rate, so that Sortino ratios greater than zero show that a fund has at least

beaten inflation.

Risk profiling

For many years since the implementation of the FAIS Act, there have been debates about the

definitions of “risk,” “risk profile” and “risk profiling.”

From the point of view of financial advisers, risk profiling is not optional – the General Code of

Conduct (GCOC) requires intermediaries to take into account a client’s ability to bear any risks

associated with a product and the extent to which a client is able to understand the risks involved in

an investment (see Sections 7 and 8 of the GCOC). Risk assessment must be considered before

advice is given.

In discussing risk with a client, an intermediary must explore three distinct risk elements:

risk required, risk capacity, and risk tolerance (sometimes called risk appetite).

R Risk required: the level of risk that needs to be shouldered in order to achieve a set financial

objective over a defined period (eg, the necessary rate-of-return) – this assumes that higher

returns can only be achieved with higher risk.

R Risk capacity: the degree to which an investor’s financial resources (both income and

existing capital) will allow the investor to shrug off market downturns and remain invested

(eg, a client must have sufficient assets, cash and income security not to be forced out of long

term investments).

R Risk tolerance: both the investor’s willingness to be exposed to market volatility (the danger

of capital losses) and the investor’s “nerve” – the ability to go the distance without panicking

during downturns.

Clear definitions of the terms “risk” and “risk profiling” are not included in the GCOC,

possibly because these words mean different things in the investment, life insurance and short term

insurance contexts.

Profile’s Unit Trusts & Collective Investments September 2025 115