Page 116 - Profile's Unit Trusts & Collective Investments - March 2025

P. 116

CHAPTER 6

The Sharpe ratio is a direct measure of the amount of reward for each unit of risk. It helps to

answer the logical question: was the return achieved worth the amount of risk taken?

The calculation of the Sharpe ratio can be thought of in two steps.

Step one is the calculation of a portfolio’s “excess” return above that of a “risk-free”

investment. This is calculated by taking a portfolio’s average annual rate of return and subtracting

a risk-free interest rate. This figure shows the “excess” return that a fund has achieved, and is also

known as the “risk premium”.

Step two shows the relationship between the risk premium and the level of risk taken. This is

calculated by dividing the excess return by the fund’s standard deviation. Obviously, the higher the

Sharpe ratio the more favourable the risk/reward profile of the portfolio.

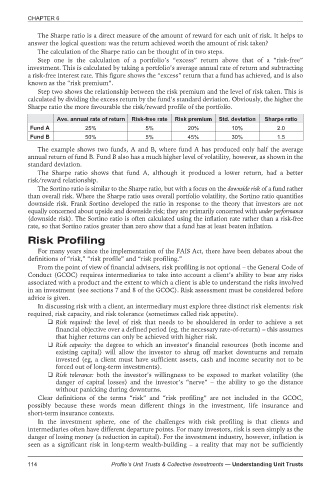

Ave. annual rate of return Risk-free rate Risk premium Std. deviation Sharpe ratio

Fund A 25% 5% 20% 10% 2.0

Fund B 50% 5% 45% 30% 1.5

The example shows two funds, A and B, where fund A has produced only half the average

annual return of fund B. Fund B also has a much higher level of volatility, however, as shown in the

standard deviation.

The Sharpe ratio shows that fund A, although it produced a lower return, had a better

risk/reward relationship.

The Sortino ratio is similar to the Sharpe ratio, but with a focus on the downside risk of a fund rather

than overall risk. Where the Sharpe ratio uses overall portfolio volatility, the Sortino ratio quantifies

downside risk. Frank Sortino developed the ratio in response to the theory that investors are not

equally concerned about upside and downsiderisk; they areprimarily concernedwith under performance

(downside risk). The Sortino ratio is often calculated using the inflation rate rather than a risk-free

rate, so that Sortino ratios greater than zero show that a fund has at least beaten inflation.

Risk Profiling

For many years since the implementation of the FAIS Act, there have been debates about the

definitions of “risk,” “risk profile” and “risk profiling.”

From the point of view of financial advisers, risk profiling is not optional – the General Code of

Conduct (GCOC) requires intermediaries to take into account a client’s ability to bear any risks

associated with a product and the extent to which a client is able to understand the risks involved

in an investment (see sections 7 and 8 of the GCOC). Risk assessment must be considered before

advice is given.

In discussing risk with a client, an intermediary must explore three distinct risk elements: risk

required, risk capacity, and risk tolerance (sometimes called risk appetite).

Risk required: the level of risk that needs to be shouldered in order to achieve a set

financial objective over a defined period (eg, the necessary rate-of-return) – this assumes

that higher returns can only be achieved with higher risk.

Risk capacity: the degree to which an investor’s financial resources (both income and

existing capital) will allow the investor to shrug off market downturns and remain

invested (eg, a client must have sufficient assets, cash and income security not to be

forced out of long-term investments).

Risk tolerance: both the investor’s willingness to be exposed to market volatility (the

danger of capital losses) and the investor’s “nerve” – the ability to go the distance

without panicking during downturns.

Clear definitions of the terms “risk” and “risk profiling” are not included in the GCOC,

possibly because these words mean different things in the investment, life insurance and

short-term insurance contexts.

In the investment sphere, one of the challenges with risk profiling is that clients and

intermediaries often have different departure points. For many investors, risk is seen simply as the

danger of losing money (a reduction in capital). For the investment industry, however, inflation is

seen as a significant risk in long-term wealth-building – a reality that may not be sufficiently

114 Profile’s Unit Trusts & Collective Investments — Understanding Unit Trusts